I have a complex relationship with Ireland. I was born there, I grew up there, I lived there until I was eighteen and I still hold an Irish passport. I have family and friends there whom I care very deeply about and I enjoy visiting there very much. But I’ve never felt an attachment to the place – try as I might. This isn’t because I was unhappy when I lived there – very far from it, in fact. It’s just that I think I knew for a very long time that my future did not lie there. I left Ireland in 1999 and, apart from visits there – holidays, really – I haven’t lived there since. The country I left behind has changed beyond recognition in that time. With the introduction of the Euro, the currency changed. The Celtic Tiger phenomenon saw the economy boom and the level of wealth and spending grow massively – unrecognisable from the poor country I remember from my childhood in the 1980s. Dublin, my hometown, was developed and gentrified and expanded. There was immigration that brought a cultural diversity to Ireland that simply had not been there when I was growing up – something I think the country has certainly benefitted from. And then, the Credit Crunch brought it all crashing down again. When I was a child, I remember that people would leave for England or America or Canada because there were no jobs – there was a drain on youth and talent. I left for a different reason: I wanted to study a subject that was not offered in Irish universities, so leaving was my choice and not a decision shaped by forces I could not control. I left at a time when things were looking up: there was work and money and people did not have to leave. I remember when I finished school at the age of eighteen that there was a sense of optimism amongst my friends – perhaps there always is when you’re that age. Of all my friend group, there was only one other who was planning to leave Ireland. That changed again after the Credit Crunch, and I remember speaking to young Irish people I met in London who, again, had left not because they wanted to, but because they needed to in order to survive. Despite all the smiles and laughs these conversations would contain, there was something intrinsically sad about this.

Irish literature and culture has been infused by this sadness – we have always been a nation of emigrants – and this has fed into some of the richest creations of Ireland’s writers, poets and painters. Travel around an area like West Cork, which I’ll be writing more about soon, and you’ll see this take physical form: historically a poor area that was home to subsistence farmers, the area was ravaged by the (entirely man-made and preventable) famines of the 1840s and 50s. Ruined buildings – often almost fully reclaimed by nature and sometimes barely still visible – dot the landscape and were home to poorest of the poor: people who left out of desperation or whose family lines simply died out with them as they succumbed to hunger.

Whilst Irish cultural identity is surely informed by generations of loss, little has fed back into our culture of the experience of those who leave and try to cling onto their identity. There are plenty of stories about those who leave and succeed – or fail – but what does it mean to leave and then return? When I go back to Ireland now, I don’t feel like it is the country I left – I’m more like a tourist there. In many ways, this makes perfect sense – time and the world does not and should not stop for one person – but it does leave me with a disconnect. Perhaps I should somehow feel more ‘Irish’ – whatever that means – than I do? For me, this is not an existential issue – though of course, I do often think about it. I’ve made my home abroad and I’m happy here – I don’t really need to feel Irish anymore. But I know there are many people – I can think of people I know personally – who have had a different experience. Perhaps things haven’t worked out so well for them and they cling on to their Irishness as a result? What if you yearn for a place or a time that simply no longer exists? What if you base your identity on something that has simply gone away?

This may seem like an indulgent diversion, but I take it very seriously. These thoughts have framed my relationship with Ireland for over twenty years and, in some way, shape or form, seep through into every serious piece of work I try to undertake there. Landscape photography may seem an unlikely conduit for these emotions, but in many ways, when I photograph a place, I’m trying to get to know that place, to get a feel for it and to convey the emotions and the feelings I experience when I am there. Perhaps with that context, the link is not so unlikely?

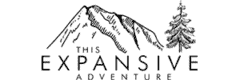

Image ID: A series of three square format black and white images. The images are grainy and have been made on film. This sequence shows the stages of a powerful wave approaching and breaking on coastal rocks. The images are very dark, but there is also bright white in the frothing ocean.

Recently, I’ve returned to a set of images that were made close to four years ago. I’ve made a fresh edit and worked up a number of selects from the series. In some ways, it’s been a frustrating process: I’m seeing compositions that are ‘almost there’ – images that to my eye would be so much better if only I’d composed them slightly differently. However, it’s also been an interesting exercise, first because I’d pretty much completely forgotten about these images until very recently, but also because I started to realise the choices I was making in editing and finishing were very different to the choices I would have made had I worked on the images when they were originally made. I realised that something of how I am now was influencing a project I started a long time ago. Looking at the finalised images from the set, I’ve started to wonder how much our culminative life experiences and mood at a certain time inform our decisions and processes as image makers. This, in turn has caused some interesting realisations into my own creative process.

But let’s step back a little bit. One of my best friends lives on the Beara Peninsula in Co. Cork on the South West coast of Ireland. I’d met this person when I was twelve when we started off in the same secondary school, back when we both lived in Dublin. At some point, we became firm friends and we’ve stayed that way ever since. Soon after we finished school at the age of eighteen, I moved to the UK and my friend headed to the Atlantic coast of Cork. His Father had lived there all the time we’d attended school together and I’d visited with him a number of times – so I was already sort-of familiar with the area. My friend always seemed happier there, and I wasn’t surprised that he relocated to that part of Ireland after we’d finished in school (in fact, his home there and his experience as an early adopter of an electric vehicle has already been the focus of an article on here). Back in September 2017, Fay and I were invited to his wedding and gladly travelled over.

Of course we brought our cameras. 2017 was before we’d made the decision to concentrate full-time on our photographic work and, as such, the way I worked back then was very different: I was working primarily in black and white with a medium format film camera. I returned from that trip with thirteen exposed rolls of film and, as I’ve always done, home-processed them. I haven’t printed in a darkroom for decades so, for a long time, my workflow with film has been a hybrid of analogue and digital processes. First, I make an edit by identifying the best frames from the negatives (one of my first jobs was working in a news photography agency and there was no time for contact prints there, so I learned to assess and select images by looking at the negatives). I’ll often photograph a scene from different angles and with different lenses, so I’m looking at composition here, but I’m also assessing the density of the negative (eg, will one frame give me better detail in the sky relative to another), and of course sharpness, which I assess through a loupe magnifier with the negative sheet laid out flat on a lightbox. Scanning is a slow process – or expensive if you send it out to a lab – so I try to be ruthless with my edit. Once I have my edit nailed down, I scan only the selected negative frames and then set final contrast (and colour when appropriate) on the digital files – this takes the place of the printing work I used to do in the darkroom.

But none of this happened with my images from West Cork. After they were processed, the negative sheets were filed in a folder and, essentially, forgotten about. There’s a number of reasons for this: shortly after that trip, Fay and I made the decision to start working together collaboratively on what would become FM Doyle and would later develop into where we are now, and this decision meant that I needed to start focussing on new, colour work. But there’s also a more mundane reason: my film scanner broke down.

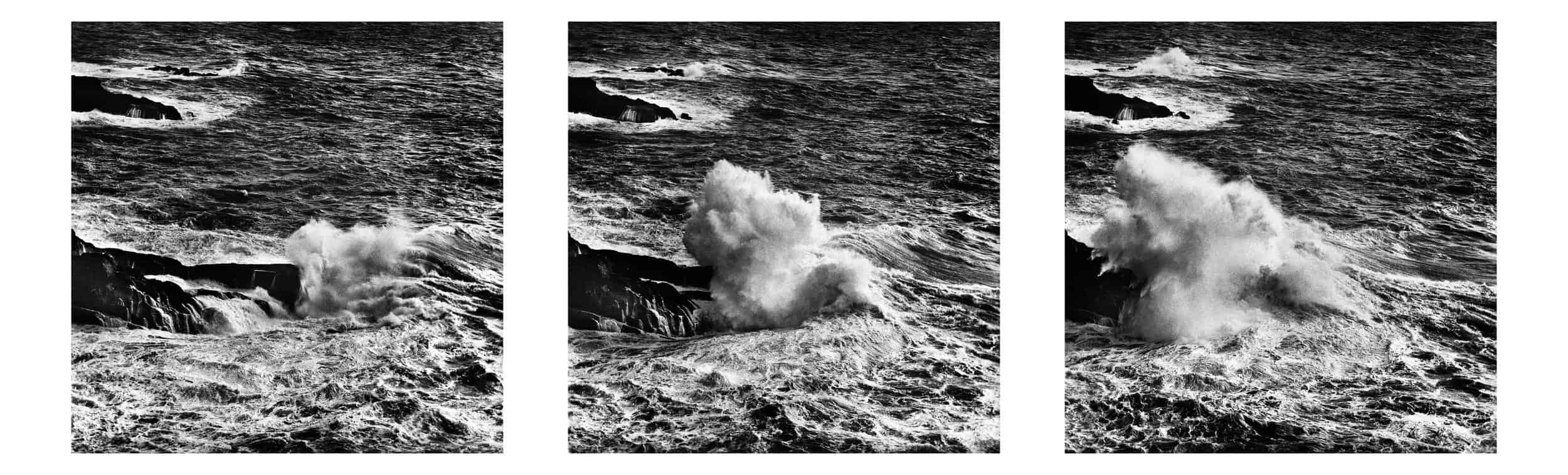

Image ID: A series of three square format black and white images. The images are grainy and have been made on film. These are images of sea cliffs through which we get glimpses of the ocean beyond. The rock is very dark with regular bright patches. In the first and third image, we can see a distant dark sky and bright waves crashing through the frame of the cliffs. In the second image, the sun sets behind a natural rock arch with a frothing sea below.

For several years, my scanner – which was now beyond its service life, couldn’t be repaired by the manufacturer or the main equipment repair centres. It just sat on a shelf. In Summer 2021 I decided I needed to see once and for all if it could be fixed. With the help of a very dedicated online DIY repair community, I was able to identify the fault (a failed IC on the power supply) and work out a plan to fix it that may involve learning how to solder. I also discovered that it would still intermittently power up, so, for the first time in years I had a (sort of) working scanner. Determined to make use of it whilst I could, I opened up my most recent negative folder and saw the sheets from West Cork. Why not start there!

September is not the ideal time to visit West Cork. It also isn’t the worst. The day we arrived, I remember looking out the window of the apartment we were staying in at a grey landscape battered with rain. Fortunately, the weather changed, and, whilst it wasn’t as good as it probably was a month or so earlier, we still had several clear, if slightly wet days. We had a great time at the wedding and, in the few extra days we had booked there, we explored the surrounding area. That part of Ireland’s coast is comprised of a series of long narrow bays – essentially fjords if you look at them on a map. These bays can provide sheltered conditions – even semi-tropical micro-climates in places – but, conversely, there are areas that are subject to the full force of the Atlantic Ocean. In a short drive along the coast you can go from gentle sheltered bays to stretches of shore that are relentlessly hammered by enormous waves – waves that you could easily imagine swallowing a ship whole (indeed, it was these same waves that claimed so many ships from the Spanish Armada in 1588 – I remember learning in school that the origins of several Spanish surnames that have a long history in Ireland can be traced to survivors from these wrecks).

The history on this coast runs far deeper than the Spanish Armada: there are numerous prehistoric sites dotted along the coast, along with remnants of past homesteads as mentioned at the start – perhaps left over from the Famine years or a legacy of emigration. But one of the most interesting things lies out at sea: look out to sea at points and you’ll notice a small dot on the horizon. That is Skellig Michael. It’s a tiny rocky island, well off the coast and subject to the Atlantic’s full fury. Though uninhabited today – well, apart from seabirds and especially Puffin – it housed a monastic community in the Middle Ages and, by virtue of its isolation, was never found and raided by the Vikings. Thus, its treasures and library survived. The Vikings were after gold and jewels, but they’d burn libraries as they raided and, in an era before printing, many texts were lost for ever. Today, Skellig Michael is recognised as a location where Classical Knowledge – essentially texts from Ancient Rome and Greece – survived during the Dark Ages. So, that little dot on the horizon is more important than you may think! If you’ve never heard of it, it’s worth a search to find out more: the monk’s stone ‘cells’ – almost like bee hives – are particularly interesting. Bringing things right up to date, you may also recognise it as the CG-augmented location where Rae tracks down Luke Skywalker in the newer Star Wars movies.

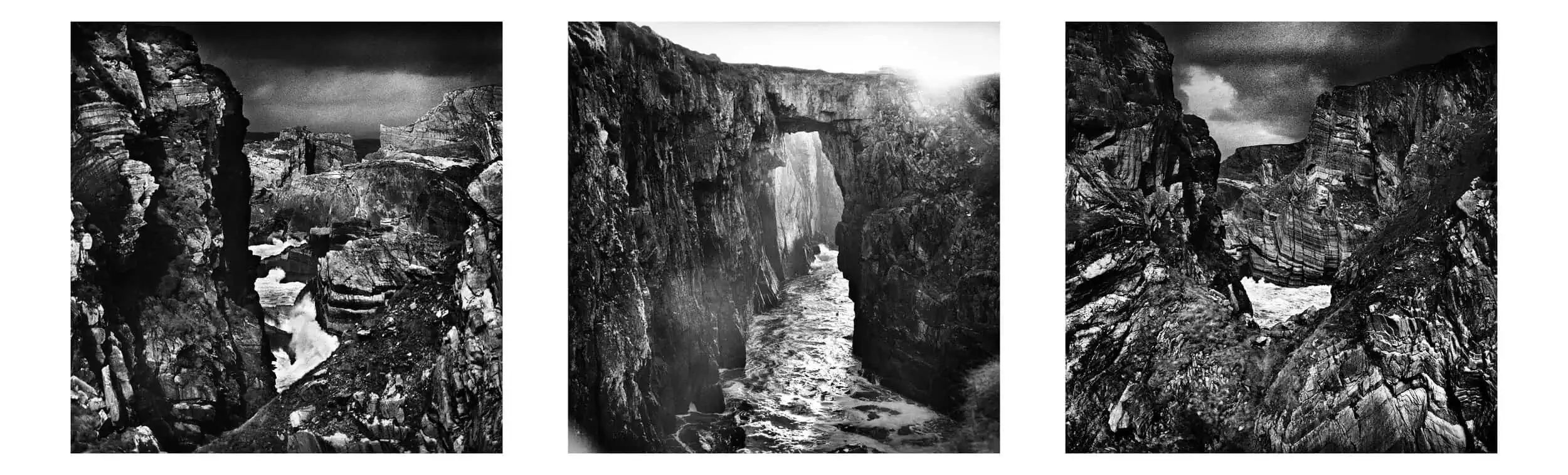

Image ID: A series of three square format black and white images. The images are grainy and have been made on film. These are images of the Atlantic coast of West Cork. There are dark brooding skies in all images and bright white waves crash against the rocks throwing a haze of water spray skywards. In the second and third image, Skellig Michael is just visible on the horizon.

Aside from time spent on the coast, we headed inland to Carrauntoohil which, at 1038m, is the tallest mountain in Ireland and also the Killarney National Park. The South West of Ireland is undeniably beautiful and visiting in September gave us a very particular perspective on it. There were brooding skies and it always seemed like we were moments away from a downpour that never quite happened. At the same time, the dark clouds would occasionally be punctured by shafts of brilliant sunlight and the contrast of this light was further emphasised by general gloom that invariably surrounded it.

Despite the fact that we were there for a happy event and spent a lot of time surrounded by good friends and new acquaintances, I was acutely aware of a certain sadness in the landscape – that was certainly my own mindset and preconceptions feeding into my process, but these instincts cannot, I think, be ignored. I don’t make field notes about my work. I know there are who some who make methodical records of exposure settings, filters used, intended processing – even notes on post production or printing that will inform the final image. I completely understand this. But this approach is not for me. I tried it and it slowed me down too much. Also, when I did manage to force myself to make notes, I found them to be of little actual use later on. Of course, I don’t remember what was going through my head when I was stood on Cork’s Atlantic coast or confronted by a break in the clouds on the approach to Carrauntoohil four years ago. I don’t remember, for certain at least, what exposure settings I used, what filters I selected and why or even – sometimes – what lens was used. But I do have the physical artefact of that moment – the negative – available to me, and I can work backwards to deduce and reconstruct the moment, and the decisions I made on how I wanted to represent it based on what I produced.

Over and under exposure have connotations of being errors amongst photographers – a mistake you make when you don’t know what you’re doing. But this isn’t right at all. Personally, I think the idea of the ‘correct’ exposure is a bigger mistake! Your exposure is the most fundamental of your creative choices in photography. Your exposure choices have many implications, but to strip it down to bare essentials, it’s a decision about how dark or light you want your final image to be. Again, some photographers will bracket – make a range of exposures and select the ‘best’ one afterwards. There’s a time and place for this, but I believe it’s related to fine-tuning or perhaps ensuring there is detail available in a certain element. I do not see bracketing as a tool for deciding the broad strokes of the mood of the image. I learned early on to be decisive about my image-making: if I make a decision that I want a scene to look a certain way, I stick with it and expose that way. This fails sometimes, of course, but that is to be expected. When it works, it works well, I think.

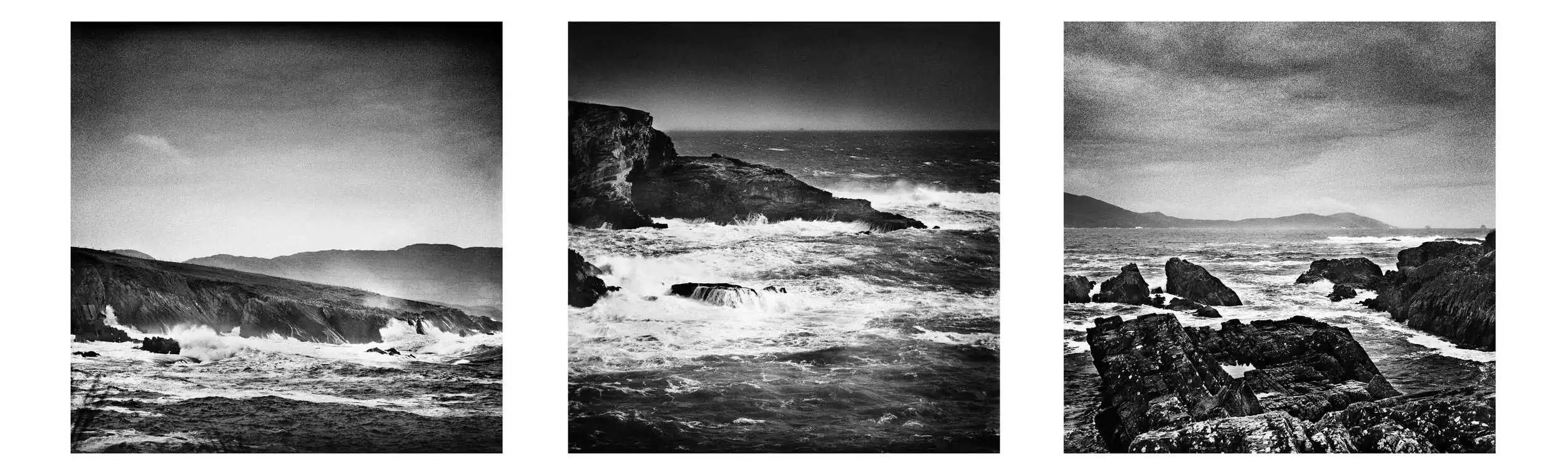

Image ID: A series of three black and white images. The images are grainy and have been made on film. These images were made inland. The first image shows the Healy Pass from a high viewpoint, a mountain road snaking through a rocky landscape. The second image shows trees silhouetted against distant mountains. Thin whisps of cloud drift over the foreground. The third image shows a valley with distant mountains a dark, brooding sky above.

My negatives were thin – under exposed. I could guess that I’d used filters – colour filters and ND grads – to make some elements less exposed still. It was clear I wanted the images to be dark. No surprises there, that’s generally my favoured approach to black and white. I could also see I’d focussed in on details, trying to isolate elements. Again, this made sense. Now, I favour working with longer lenses for this exact reason. In 2017, I was starting to make this realisation. None of these deductions were exactly revelations to me, but as I scanned the film, I started to realise just how dark I had chosen to go.

2020 and 2021 have been hard years for me. My mental health has absolutely suffered in this time. I think I’m someone who has always been prone to feeling anxious or depressed and at various times, this has impacted me deeply, but what I’ve experienced over the last year has far surpassed anything I’ve experienced before. The pandemic has undermined a lot of the certainty I previously had about the decisions I’ve made in my life. As our business effectively ground to a halt, it wasn’t long before I started questioning why I was doing any of this at all. It’s been very tough. In the past, regardless of any uncertainty I might have about how things were going, I’d always had a fundamental knowledge that I was where I was because I wanted to be there and that it was the right thing for me to do. In 2020 and 2021 I started to question this. Every decision I had to make was undermined to some extent by an uncertainty about whether or not I was doing the right thing or something I even wanted to.

For a long time, these dark thoughts greatly impeded my creativity. I could still produce images to brief, write articles, set colours and so forth, but I felt like a spark had gone. Looking at my raw scans from a rediscovered trip, I somehow made the connection that here was an opportunity to give expression to some of the tumult of feelings I had experienced.

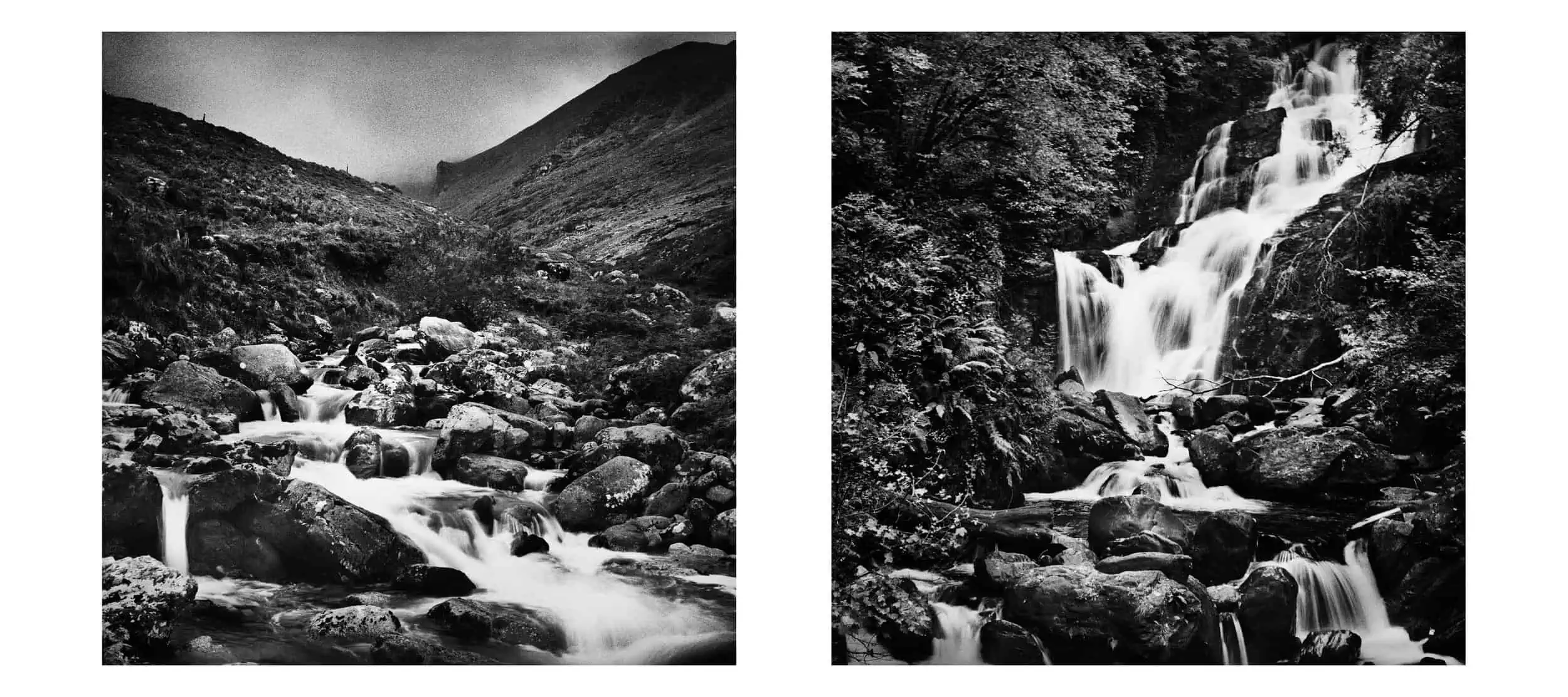

Image ID: A series of two black and white images. The images are grainy and have been made on film. These images show white-water streams with small waterfalls flowing through a dark landscape. The images are generally dark, but the flowing water, blurred through long exposure is bright white.

My landscape work has never been about creating something from scratch. I don’t create light or mood in scenes that isn’t already there, but I do emphasise or de-emphasise what’s already there – this is something that’s flowed across into Fay and I’s practice now that we work together and we’ve written about this before. Sometimes, images can go on a lengthy journey from the original scan or raw capture to the final, finished image, and I make no apologies for the fact that some of my images – whether black and white or images produced collaboratively with Fay – look stylised. But one constant is that we are always working with elements that are already present in image. Nothing is just created.

This process is deceptive. It’s not just about dialling up the contrast or turning down the brightness. The images still need to communicate a sense of place. Contrast and darkness kill detail – whether that’s shadows blocking up or blown-our white highlights creeping into areas where you want to read detail. At the same time, if you want darkness, if you want contrast, then you have to sacrifice something to have the solid blacks and pure white. Every image is a dialogue. Ansel Adams famously likened the relationship of a final print and the negative to a musician’s performance of sheet music. Even though I’m not at all musical I think this is a great analogy. Just as a performer’s mood may influence their performance on a given night, so my mood fed into my interpretation of the information recorded on my negatives. I was mindful that I didn’t want the images to simply be dark – there comes a point, I think, when you realise that teenage angst is not enough, it needs a conclusion, a counterpoint. As I studied the negatives and worked backwards to my decisions that led up to the moment I pressed the shutter release, I began to see that I hadn’t been trying to record darkness at all, but rather the subtleties of brightness. The moments when the light broke through.

My time spent working up these half-forgotten images was certainly cathartic. My experience fed into the work I created and perhaps helped me to confront and put words to some of things I had experienced – and not just with regards to the mental health issues I’ve faced this last year, but perhaps also in terms of examining my own identity as an emigrant and immigrant. However, it did not provide any great, revelatory solutions. I didn’t expect it to. None the less, the elements aligned to help me produce a body of work I feel very proud of and also to help remind myself that perhaps the uncertainty and anxiety I have been experiencing lately is just transitory and that perhaps – perhaps! – I’m still on the right path after all.